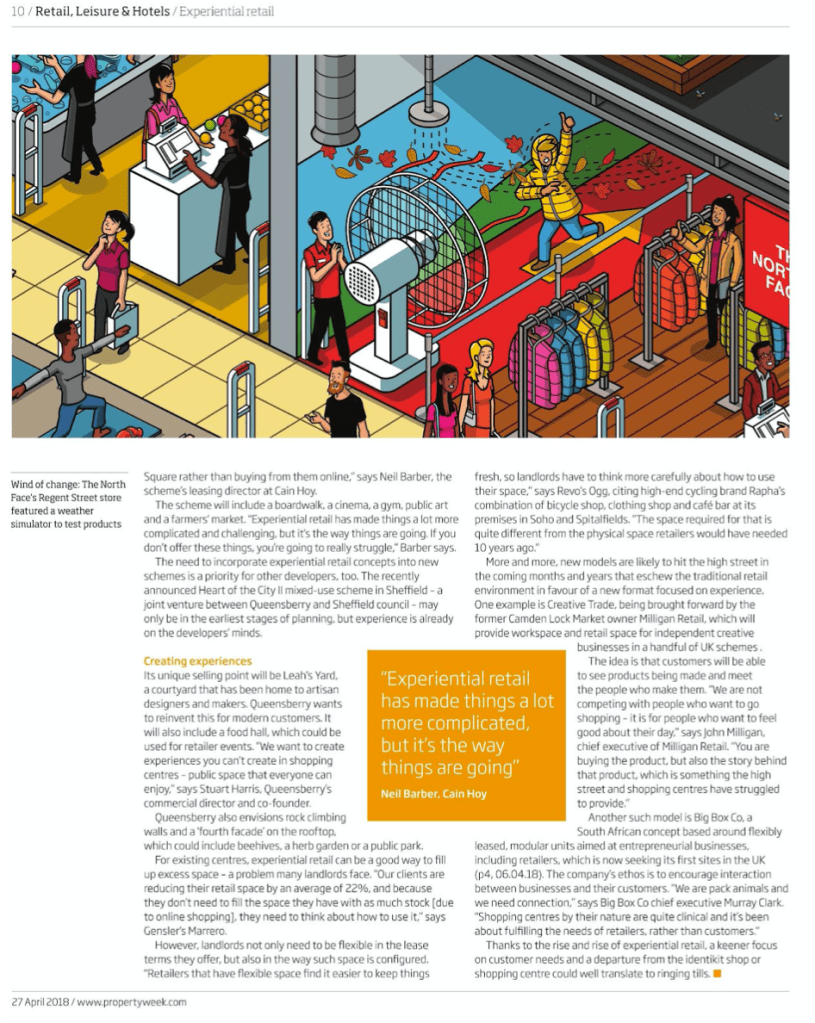

Published in Property Week, 18 September 2020

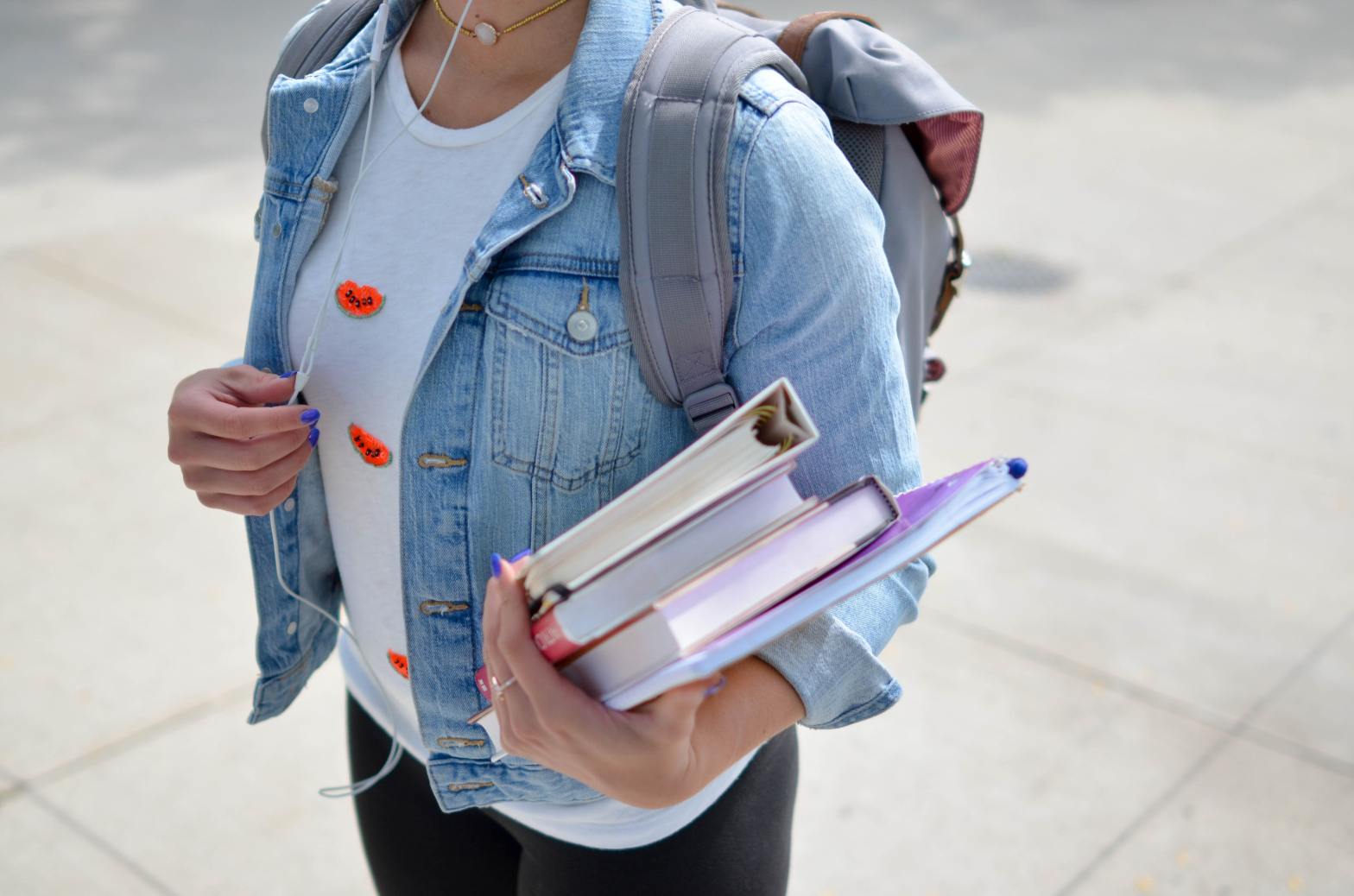

Main image by Element5 Digital on Unsplash

Imagine turning up to university as a fresher this month. You check in to your room online before you leave home and set off in your packed car alone – you have been asked to arrive solo if you can, to aid social distancing. When you arrive, there is no host of enthusiastic student reps to greet you – just a few masked people behind a Perspex screen. There are not even many other students milling around because arrival times have been staggered to aid social distancing.

You find your room, which you can open using your phone to avoid handling keys, and break the hygiene seal on the door to go inside. You know there is a Zoom social happening later that evening, but that is it as far as organised events go.

It is nothing like the communal, social week of non-stop partying that students were promised in the past – and yet they are being encouraged to go regardless. In a recent televised statement on Covid-19, prime minister Boris Johnson described the reopening of universities as “critical”.

Everything was brilliant. Then Covid came along

Tim Pankhurst, CBRE

But how many students will choose to start university during a global pandemic? And what does that mean for the £50bn purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA) sector?

Pre-Covid, student accommodation was going great guns, as evidenced by Blackstone’s pre-lockdown purchase in February of PBSA operator iQ for £4.7bn – the UK’s largest-ever private property deal.

“Student accommodation was set for a record year,” says Tim Pankhurst, senior director at CBRE. “The system had never been so oversubscribed. The population of 18-year-olds was rising again after 10 years of decline. There was really strong rental growth. Everything was brilliant. Then Covid came along.”

When that happened, most operators offered students refunds if they wanted to leave. Pankhurst says that while some schemes remained almost full – mostly due to international students unable to leave the country – others saw occupancy drop as low as 20%. “Some took a really big hit in terms of income,” he says.

For those who stayed, it was a strange experience. “We never closed our reception or turned off crucial services, but we had to close cinemas and gyms,” explains Jess Gallop, director of people at operator Student Roost. She estimates that around 8,500 of its residents stayed in situ, out of a total of 19,500.

Wait and see

Now, attention is turning to the new academic year. With most courses starting in late September or October, operators face an anxious wait to see how full their buildings will be.

Final student numbers for this year are not yet available, as clearing continues until 20 October, but early indications are not as dire as one might expect in the middle of a global pandemic.

UCAS data shows that, as of June, total applications were 2% higher than in 2019 – and that was before some students saw their A-level results change when the government abandoned its controversial grading algorithm in favour of teachers’ predicted grades.

As a result, the cap on the number of students that universities can admit has been temporarily lifted, which means numbers could well exceed last year’s. And at 5%, the current rate of deferrals is in line with 2019.

It seems that after months stuck at home, school leavers are keen to get away to university, even if they cannot yet have the full student experience. “A lot of students have decided that, although their course is going to be online to start with, they would rather be getting integrated into their new area than at home with mum and dad,” says Kevin Williamson, investment director at PBSA operator Host.

“The whole sector has been working on the basis that students are going back, and lots of them are going back.”

According to CBRE’s latest sector report on PBSA, accommodation bookings are holding up. “Although occupancy levels suffered this year, bookings for the 2020/21 academic year are now broadly in line with 2019/20,” it says, adding that headline rents have increased by around 3% in portfolio assets.

The sector may also have benefitted from a last-minute rush due to the A-level results debacle. Accommodation booking website student.com says it saw an 86% year-on-year uptick in searches on its website the day the revised results were announced.

There is a catch, however. Deposits in the sector are low (usually around £250), which means there is little to lose for no-shows. In other words, having a lot of bookings does not guarantee much.

“Do we have bums in beds? We don’t really know until lectures start,” says Pankhurst.

A particular concern is whether international students, who are vital to the PBSA market, are able and willing to travel to the UK.

“The high-end providers have upwards of 90% international residents, while the mid-range have well over half,” says David Feeney, partner at Cushman & Wakefield.

That is not necessarily a problem if there are enough domestic students to fill the beds, but they often cannot afford the prices that come with higher-end PBSA stock. There have been some reports of discounts being offered on rent, though it is not yet widespread.

“The most expensive stock seems to be offering discounts and incentives, while there has been very little discounting on lower-priced stock,” says Feeney.

To allay student fears, many operators are offering ‘no visa, no pay’ agreements, along with other assurances that students will not be held to contracts if the Covid situation changes.

Our focus this year is going to shift to mental health and wellbeing

Jess Gallop, Student Roost

Traditionally, students must sign 44- or 51-week leases on accommodation, which can only be broken if they drop out of university. But as more courses are being held fully or partly online, and some postponed until January, there is talk of more flexible leases becoming the norm. Some operators, including sector giant Empiric Student Property, are already offering single-term lets.

“Being flexible and able to adapt is key,” says Williamson.

“If you’re not, it will be detrimental to the performance of your asset.”

Assurances like these might help PBSA draw in second-and third-year students who, given all the uncertainty, are reluctant to sign a lease with a buy-to-let landlord.

“There’s a growing trend for people to choose PBSA over HMOs [houses in multiple occupation],” says Brian Welsh, chief executive of Round Hill Capital-backed operator Nido Student. “They’re better-managed, there’s more cleaning and HMOs certainly didn’t give anyone back their rent.”

Social benefits

PBSA operators will still provide some of the social aspects of halls of residence too, despite the pandemic. “Our focus this year is really going to shift to mental health and wellbeing,” says Gallop. “We’re really maxing that out because goodness knows how all this will impact our residents.”

Events will also go ahead, either socially distanced or online. For example, Welsh says Nido has hosted online yoga, quizzes, cocktail classes, magic lessons and even Friday night DJs.

So how does this affect the investment outlook for PBSA?

Financially, the sector is getting back on its feet. Unite’s share price has recovered by more than 50% from a low of £6.35, and the share prices of Empiric and GCP have recovered by 20% and 25% respectively from their lockdown lows.

“I still take calls every day with investors wanting to access the sector,” says Welsh. “There isn’t much distress at play – most assets are owned by big, institutional investors that don’t need to access that capital in the short term.”

Most in the sector are viewing the 2019/20 and 2020/21 academic years as a blip that can be overcome relatively easily – as long as Covid-19 restrictions do not last more than two years.

“For September 2021, everyone is betting on quite a big return,” says Pankhurst.

For the freshers starting university in the next few weeks and for the owners and operators of student accommodation blocks the message is the same: hunker down, get through the next year and hope that the best is yet to come.